The Baraboo River : a Story of Transformation, Adaption, and Renewal

The Baraboo River, winding 120 miles through the heart of Wisconsin, holds a rich history marked by 19th century development, change, and restoration. It stands today as one of the longest restored free-flowing rivers in the United States, a designation that speaks to both its vibrant past and the resilience of the communities along its banks. From its role as a central artery and place of settlement for Indigenous Peoples to its transformation into a bustling center for mills and dams during the 19th and early 20th centuries, the Baraboo River tells a story of ecological and industrial evolution.

Early History and Indigenous Significance

For centuries before Euro-American settlement, the Baraboo River served as a critical resource for the Indigenous Peoples of the region, including the Ho-Chunk. The river provided water, fish, and a means for transportation, and it formed part of a larger watershed that sustained the region’s biodiversity. Indigenous Peoples had deep connections to the land and water, and their interactions with the river were characterized by balance and stewardship, relying on its resources without depleting them. The name “Baraboo” is believed to have derived from the 18th Century French fur trader, Francois Barbeau, but the river itself existed in oral traditions long before written records documented its existence.

Photo courtesy Sauk County Historical Society

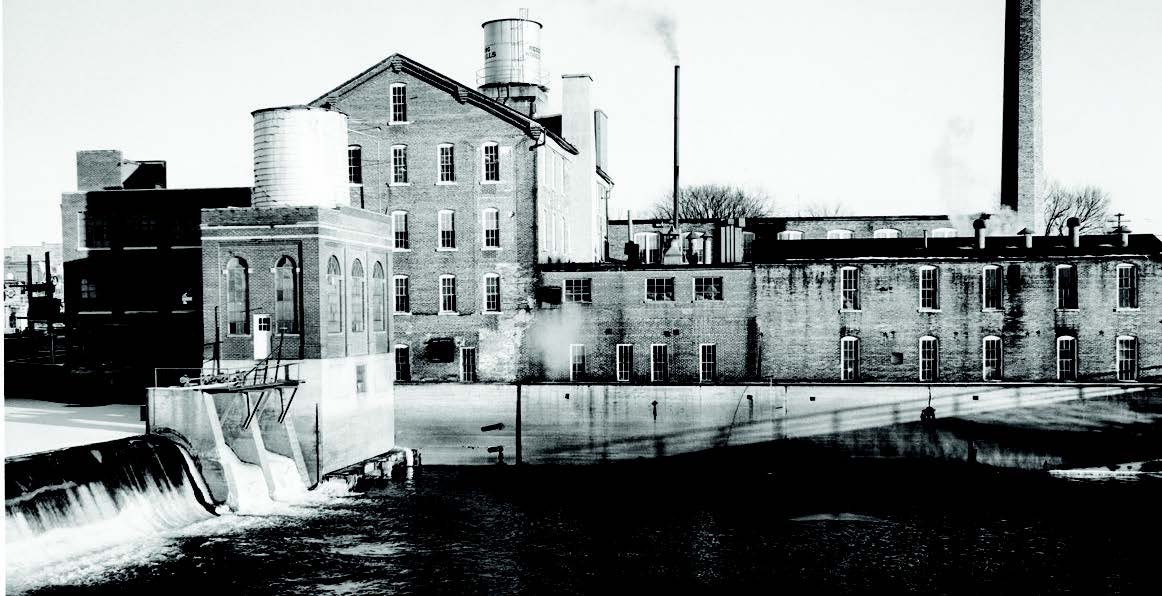

The Industrial Boom: Mills and Dams

The Baraboo River underwent significant transformation with the advent of Euro-American settlers in the early 19th century. In the 1840s early industrialists recognized the potential of the river to power mills. The flow of the Baraboo was harnessed to drive water-powered sawmills, gristmills, and other machinery, creating a boom in local industry. By the mid-1800s, numerous dams were constructed to control and direct the river’s power, capitalizing on the river’s natural flow.

The mills attracted workers and settlers, and towns grew along the riverbanks. Baraboo, one of the most prominent of these towns, became a thriving center of economic activity. Early industries capitalized on the timber and agriculture of the surrounding land, using the mills to process raw materials into marketable goods. The building of dams and millraces served as a testament to the ingenuity and industrious spirit of the period.

Environmental Impact and the Decline of the Dam Era

While dams and mills brought prosperity to the area, they also had considerable environmental consequences. The natural flow of the river was interrupted, impacting the river’s ecosystem and native fish populations. Dams slowed the river, leading to increased sedimentation and a decrease in water quality. Native fish species, which relied on free-flowing waters for spawning, saw their populations decline, while plant life and biodiversity along the banks suffered from the restricted water movement.

As the 20th century progressed, technological advancements and changing economic demands led to a decline in the need for water-powered mills. Electricity began to replace water as a primary source of energy, and many of the industries that relied on the Baraboo River moved on. By the mid-1900s, many dams had fallen into disrepair or were no longer needed for their original purposes, leaving them as relics of a past era.

Photos by Jeff Seering

Photos by Jeff Seering

Restoration and the Modern-Day Free-Flowing Baraboo River

The environmental movement of the 1970s and subsequent decades brought a renewed focus on the health of America’s rivers, including the Baraboo. Conservation groups, local residents, and environmental advocates began to push for dam removal as a means of restoring natural ecosystems. Their advocacy paid off, and between the 1990s and early 2000s, significant progress was made toward removing the dams along the Baraboo River.

By 2001, the last dam was removed, returning the river to its natural free-flowing state for the first time in over a century. This effort marked the Baraboo River as one of the longest rivers to be entirely freed of dams in the United States. The removal project was celebrated as a significant success in river restoration, setting a precedent for other communities across the nation to consider dam removal as an effective ecological restoration method.

The restored Baraboo River now supports a rejuvenated ecosystem with improved water quality, allowing fish populations and native plant species to flourish. Anglers, kayakers, and nature enthusiasts enjoy the river’s scenic beauty, and the return of vibrant ecosystems has become a draw for tourism, benefitting the local economy in new ways. The success of the Baraboo River’s restoration is a shining example of how communities can work together to reclaim and honor their natural resources, respecting the balance that was once maintained by the river’s earliest stewards.

The Beauty and Future of the Baraboo River

Today, the Baraboo River winds through lush landscapes and small towns and villages, and through the cities of Baraboo and Reedsburg, showcasing Wisconsin’s seasonal beauty. In spring, wildflowers bloom along the riverbanks, and in autumn, vibrant foliage reflects on the water’s surface. Recreational trails and parks now line portions of the river, encouraging outdoor activities that bring residents and visitors closer to nature.

The story of the Baraboo River is one of transformation, adaptation, and renewal. Its return to a free-flowing state has not only restored an important ecosystem but has also rekindled a connection between the river and the people who live near it. As conservation efforts continue, the Baraboo River stands as a living testament to the power of restoration, offering a hopeful reminder that nature, when given the opportunity, can rebound in breathtaking ways.

Through the centuries, the Baraboo River has shifted from a natural waterway to an industrial powerhouse and back to a thriving ecosystem. It remains a beautiful and vital part of Wisconsin’s landscape, a reminder of both the possibilities of progress and the importance of stewardship.